Pandemic preparedness: pathways to resilience through global health infrastructure

The time has come for a long-term approach to investment in health infrastructure.

Given the strong likelihood of another pandemic occurring, now is the time to act on the lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic to improve health infrastructure and our global health ecosystem.

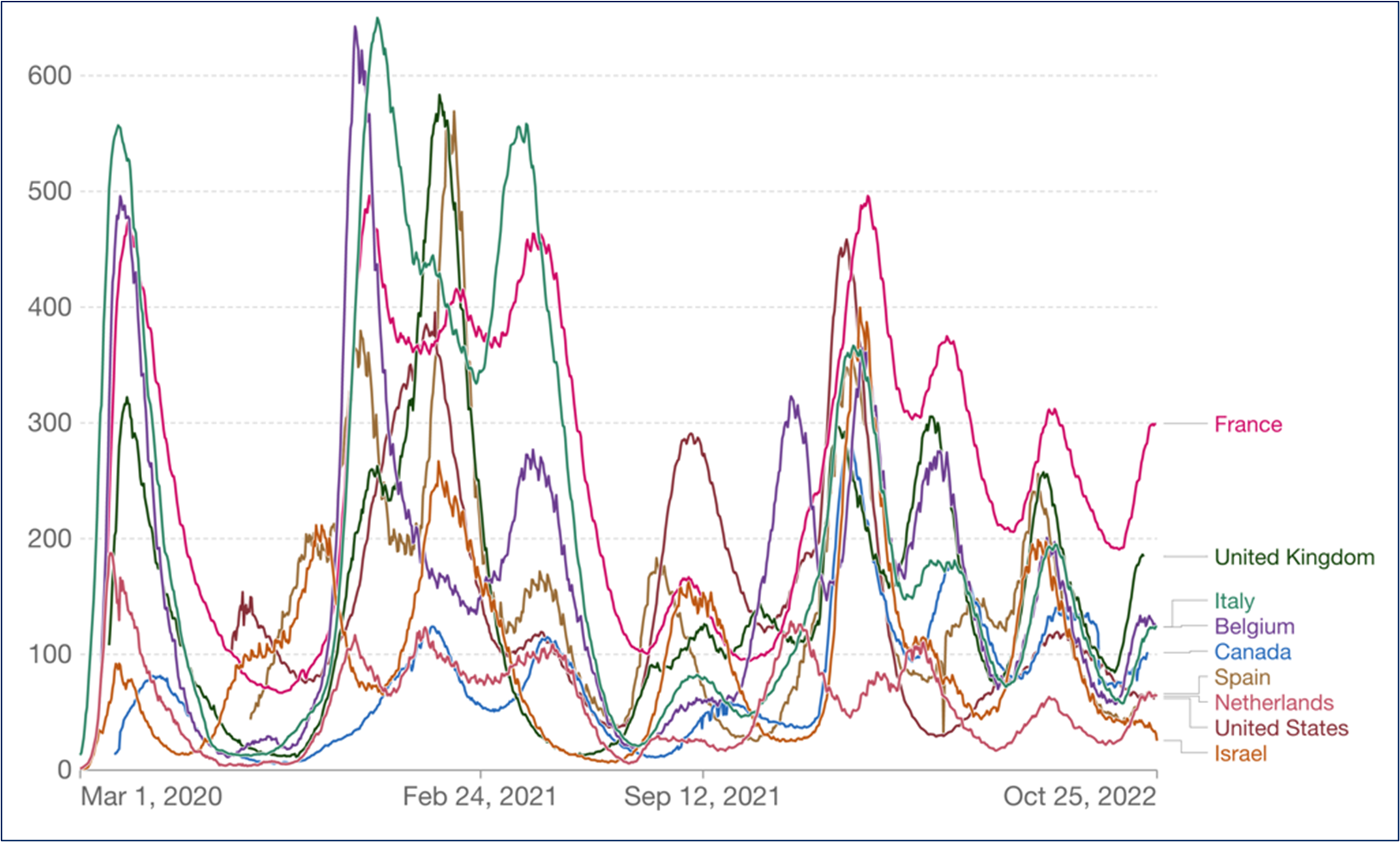

At the time of writing, the WHO estimated around 6.5 million deaths and around 610 million cumulative cases of COVID-19 worldwide. According to the Global Change Data Lab, for every million cases of COVID-19, the number of patients requiring hospitalisation fluctuated from 600+ per million at the heights of the pandemic to 100 - 300 per million currently (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of COVID-19 patients in hospital per million. Source: Official data by Our World in Data – last updated 25 October 2022. Our World in Data

This incidence was also reflected in demand for intensive care unit (ICU) beds (see Figure 2 below), putting a massive strain on health systems and health professionals, who often operate near, at, or even beyond capacity and capability.

Figure 2: Number of COVID-19 patients in ICU per million. Source: Official data collated by Our World in Data - last updated 25 October 2022. Our World in Data. Note: For countries where the number of ICU patients is not reported, Our World in Data displays the closest metric (patients ventilated or in critical condition).

However, this increased demand for beds was met by a state of inadequate health system capacity, particularly in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDEs). As recently as 2017, half the world lacked access to essential health services. For example, many countries in Africa have limited health infrastructure and workforces, including a shortage of professionals trained in critical care and inadequate ‘tertiary care facilities’ (specialised hospitals). In urban Africa, health facilities are overcrowded with patients due to staff shortages, while in rural areas, unreliable transport and poor roads infrastructure remain key bottlenecks for access to medical care. These issues, many of which are directly or indirectly driven by lack of suitable infrastructure, severely hamper pandemic responses.

Even advanced economies were caught by the pandemic, with many developed countries having to rapidly mobilise surge capacity, convert non-critical beds to critical care, and postpone elective surgeries.

Adequate infrastructure investment is critical to health system capacity and, by extension, pandemic response and management. This is particularly true of EMDEs, in which lower levels of existing infrastructure exacerbates their capacity to respond to pandemics. This has been demonstrated by clinician-researchers working in developing countries in the Pacific. In an article published in July 2022 they found that: 'Investing in adequate infrastructure and appropriate equipment is crucial for an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The sustainability of such investments in the Pacific context is paramount for ongoing emergency care and preparation for future.’

Put simply, infrastructure investment that improves health system capacity is fundamental to managing the next pandemic.

However, measuring health system capacity is complex. Bed capacity is an imperfect proxy for capacity. This is because bed capacity is a complex amalgam of physical infrastructure (hospitals and equipment), human capital, and labour (clinical and non-clinical staff). All infrastructure requires ongoing labour, even if only for maintenance. However, health infrastructure is among the most labour-intensive infrastructure category, as it requires many highly trained staff working in combination with infrastructure investment to be effective.

For this reason, a conversation about health system capacity must focus on infrastructure and the trained staff that use and maintain it. Only with this holistic view can we begin to understand the quantum and value of optimal investment. Furthermore, while less visible, another ‘casualty’ of pandemics is non-critical care - triaging in healthcare means interventions that are less critical are delayed because more critical interventions demand priority of available resources.

Moreover, health infrastructure is not the only infrastructure category that impacts pandemic preparedness. Funding must radiate beyond the boundaries of the hospital to consider other vital contributors to the health of a nation and the resilience of its health system. Recent OECD research on the role of development finance in strengthening health systems for future pandemics found that '[the COVID-19 pandemic] engulfs systems as a whole, especially in low-income countries where they are most fragile. It is important to step up support to universal health coverage and avoid the disruption in other critical care health provision.'

For example, poor road and transport infrastructure is a significant barrier to accessing critical care in many rural areas. Water infrastructure is also a key element of population health. The WHO and UN-Water found that each USD1 invested in water and sanitation in developing countries yields USD4.30 of benefit through avoided health costs, as well as non-health benefits for the environment, education, and productivity. The value of avoided health care costs could be reinvested into providing better business as usual care - providing a higher baseline to surge from during a pandemic.

The best time to start planning for the next pandemic is now. Infrastructure investment is critical to building resilience and improving our pandemic readiness, particularly for countries with already vulnerable health systems.

G20 Pandemic Fund will change the global health landscape for the better

G20 Pandemic Fund will change the global health landscape for the better